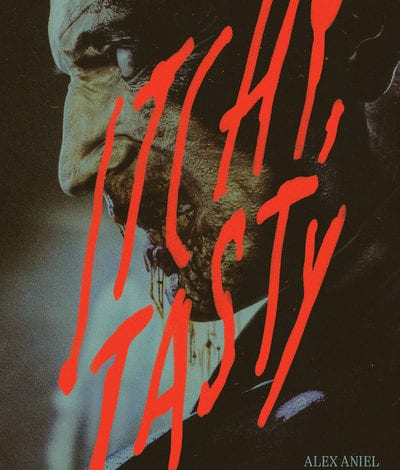

Itchy, Tasty: An Unofficial History of Resident Evil Review

The following is a review of the Kindle edition.

A darling of early 3D console gaming, Resident Evil not only established survival horror as a proper genre, but it shaped and developed 3D gaming as a whole. Alex Aniel’s Itchy, Tasty: An Unofficial History of Resident Evil provides an intimate look back at the series’ early development, starting from Capcom’s Sweet Home and ending with Resident Evil 4. It’s a cleanly written narrative, highlighting both how experimental the series was and how not every one of those experiments panned out. Everything from the mainline games to the canceled spin-offs are discussed, and there’s a chapter here for just about every breed of Resident Evil fan (SEGA fans included).

Compared to Mega Man and Street Fighter, the first Resident Evil was a more immediate success, putting it ahead of Capcom’s historical curve.

The book opens with a brisk history of Capcom as they existed in the 1980s and 1990s, and how they came to find success with platforming games and licensed properties. A brief overview of SEGA and Nintendo’s 16-bit mudslinging match is given, though if you aren’t a child of the era, the greater context may be lost upon you. Street Fighter II is also discussed, building an image of what this Japanese development house was like in its heyday, and furthermore, how surprisingly dire Capcom was just prior to the original Resident Evil’s release.

Aniel gives some background on how he got into the industry, his love of the Resident Evil franchise, and how his fluency in Japanese not only got him in close contact with many of the series’ key players, but how several of these interviews happened seemingly by chance. Aniel mostly keeps himself out of the story after the first few chapters, other than popping in for certain interview anecdotes. This is nice, as it keeps the focus on Resident Evil and not his fandom. However, he also inserts some interesting observations about the subjects on a personal level, like when he stresses how kind Hideki Kamiya is, despite his rather intimidating online persona.

The next few chapters waste little time in getting readers familiar with important figures like Tokuro Fujiwara, Shinji Mikami, and Kamiya. Because the first Resident Evil game was so experimental in design, Aniel dedicates an appropriate amount of time discussing development hardships, as well as the tense atmosphere at Capcom. He also delves into the wonderful disaster of a script, explaining how the developers were literally flying by the seat of their pants in making the scenario come together. The game’s infamous live-action cutscenes and voice acting are explored, with the disconnect in language and instruction between the Japanese producers and American actors leading to delightful accidents like the infamous “Jill Sandwich”. Furthermore, it highlights just how much Capcom relied on stereotype and cliché for the first game, serving as an interesting contrast to how the series’ narrative and characters would evolve.

The game’s unexpected success leads into the proceeding chapters, which cover everything from the equally troubled Resident Evil 2 (or 1.5, as fans commonly refer to it) to the Resident Evil mania that took hold of the video game industry shortly thereafter. Rushing to get sequels greenlit, switching spinoffs to mainline games, and preparing for the new console generation are all discussed. The book features a number of stories that I had never heard, including Resident Evil’s surprising connection to a Napa Valley winery, and it’s cool that Aniel was able to get so much behind-the-scenes information from the developers.

Japanese game companies have not always been so forthcoming with their history. In the 1980s, Capcom and some of its competitors had been so secretive that pseudonyms had been used in game credits to prevent the aggressive headhunting of talent in what was then an immature industry.

That said, the focus is rather constrained, and it would have been nice to see Aniel try and track down some of the other talent involved, getting insight into what development was like from the perspective of a graphic designer or programmer instead of focusing almost entirely on the directors and managers. Bits like the door mechanic used to hide loading times are mentioned, as is its continued application after such restraints were no longer necessary. The choice to settle on pre-rendered environments as opposed to fully polygonal ones is also touched upon, though I wish there had been a bit more on the design process from both artistic and technical angles.

…despite Capcom’s initial low expectations for Resident Evil 3: Nemesis, Resident Evil fans’ positive response to the title ultimately legitimized it.

About a third of the way through the book, the narrative switches tracks to explore how the Resident Evil series existed on different platforms, including Nintendo, handheld, and SEGA consoles, followed by chapters dedicated to the spin-off games, like Survivor and Outbreak (Curiously, Aniel doesn’t delve much into the PC ports.) These middle chapters are among the most enjoyable in the book. As a fan who came to love the series via the Dreamcast ports of 2 and 3, but who honestly doesn’t enjoy Code Veronica (Jill didn’t need to a press a button to use the stairs in 3, why does Claire need to in Code Veronica? Unacceptable.), I very much enjoyed learning about Code Veronica’s storied development, and how risky it was for Capcom to outsource such a monumental title at such a critical point in the series’ uncertain future. Furthermore, the section on Gun Survivor 2: Biohazard – Code Veronica is fascinating, and it was interesting to learn about SEGA’s role in bringing the series to the arcades alongside frenemy Namco.

The chapter dealing with Nintendo, however, is the most pivotal, as it sets up the book’s final section. Capcom’s choice to prioritize the GameCube above its competitors (the PlayStation 2 and Xbox) remains both confusing and fascinating, as these years were both defining and deeply troubling for Capcom. Aniel explores the uneven development of Resident Evil 0 and its journey from the Nintendo 64 to the GameCube, but the reasons for Capcom’s support of Nintendo seemingly went deeper than sunk-time justifications or financial gains. In fact, the reasoning struck me as noble and principled in a way game development simply isn’t nowadays. It was a real trip back in time, and made me remember just how much ideology, and hardware, differed between companies.

It all culminates in the development and launch of Resident Evil 4. Though it works as a great climax, the details regarding Resident Evil 4’s various incarnations are, sadly, barely explored outside of information already available (i.e., trailers and old interviews). What did the game play like when Kawamura had been going for the hallucination angle? What was the story like before Mikami went hands on? The answers to these questions, it seems, are still locked in a vault somewhere, and Aniel may just not have had access to them.

The “Hallucination” concept had proven to be unfeasible on GameCube hardware, which made Mikami aware of the perils of basing a game’s concept around a single story point.

And then, it ends. Clover and Platinum are briefly discussed, but the unofficial history of Resident Evil ends at 4. The book was originally funded on Unbound.com, and its scope was made clear in the campaign. That, and with the fourth entry near-universally considered to be both a monumental leap for game design and one of – if not the – best entry in the series (not to mention the last Resident Evil title Mikami worked on), it’s hard to argue that Resident Evil 4 isn’t a fitting place to end.

Though the book is filled with behind the scenes information, how much of it is revelatory will depend on your level of fandom. We don’t learn much new information regarding the various Resident Evil 4 builds, nor is 1.5’s campaign discussed in great detail.

With Resident Evil causing such huge ripples in the industry at the height of its popularity, it spawned countless knock-offs (including SEGA’s own Deep Fear). The tweaks and alterations these games made to the Resident Evil formula are not explored, nor is the broader impact of survival horror on the industry (aside from a passing mention of Konami’s Silent Hill and its influence on Kawamura, Fujiwara’s work on Extermination, and how SEGA’s House of the Dead encouraged Capcom to explore other genres for their franchise). Horror gaming was in its infancy here, and a chapter dedicated to Resident Evil’s impact would have been a great means to showcase just how influential it truly was.

All that said, the only reason these holes need be highlighted is because what is here is highly enjoyable, and it left me wanting more. Itchy, Tasty: An Unofficial History of Resident Evil is essential reading for any fan of Capcom’s flagship horror series. Learning about the people thrust in charge of these rapid-fire releases, and Capcom’s constant striving to find out what made Resident Evil, well, Resident Evil, is fascinating. It may not entirely satiate your hunger for information, but it’s none the less a great recount of horror-gaming’s most fascinating era.